Exploring The Timing Capabilities Of Raspberry Pi And Linux

What this is about

Many projects require accurately-timed events to pull off - for example, high precision motor control may require a motor to be stopped at an exact time, the more accurate the better. The best way to obtain accurate timing is no doubt to use a real-time operating system, which allows hard deadlines to be set for tasks, so that they will absolutely be executed by that deadline. Compare that with general-purpose operating systems, which make no such promise - planning to stop a motor at a certain time does not mean the code will actually run by that time. These features mean that RTOS is a much better choice for accurate timing.

There is, however, a problem - RTOS enjoys the best support on microcontroller-based boards, and using RTOS on the ubiquitous Raspberry Pi is rather troublesome. Is switching to a microcontroller absolutely necessary? What kind of timing performance can we expect from a vanilla Raspberry Pi + Linux combination? This article finds that out with testing on a laser-based communication project.

Experimental setup

The setup for the laser communication experiment is straightforward - a GPIO pin of the RPI is used to switch a laser module on/off, and this is used to send laser pulses that indicate 0 or 1. A short pulse for 0, a long pulse for 1. A light-sensitive diode is connected to another GPIO pin of the RPI, and triggers interrupts based on both the rising and falling of the voltage on that receiving pin. Naturally, the sender and receiver are run as different processes.

As is the case with many other time-sensitive applications, performance rises with accuracy of the timing. With more accurate timing, the laser pulses can be programmed to be shorter to increase transmission rate, until the point that random errors in the timing are as large as the difference between the short/long pulses, and the two can no longer be reliably distinguished. The more accurate the Pi’s timing control can be, the faster the data transmission. A realistic scenario, right?

In these experiments, the great majority of timing control is done with the standard C time.h library and usleep() function. Interrupt handling is done with the WiringPi library.

Finding #1: Timing accuracy is sensitive to CPU load

Unlike real-time operating systems that can pre-empt other tasks to make way for a timing-critical thread to run first, a general purpose operating system does not have this ability. That leaves the possibility of other threads “competing” for CPU time with the thread handling the timing, and preventing the laser on/off commands from being run on time. This is especially true when CPU load is high.

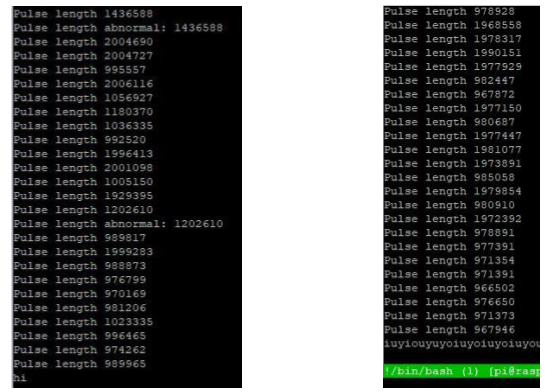

In practice, this effect was indeed observed. When only 1 CPU core is enabled, the random errors in the laser pulse timing are much more significant. When short/long pulses are set to 1ms/2ms respectively, the short pulses are regularly delayed by 200-400 microseconds, so that the actual received length becomes 1.2-1.4 ms. This precludes any possibility of shortening the pulse lengths and increasing speeds.

With all 4 CPU cores of the RPI enabled, the random errors are greatly diminished. This is probably due to the CPU load on each core being less intense, so that there are less threads that can delay the execution of the laser on/off commands. The increased accuracy leaves room for increasing transmission rate.

In the below comparison, large deviations from the designated pulse lengths are seen in the left picture (1 cpu running, high load), while the pulse lengths are mostly precise in the right picture (4 cpus running, low load).

Finding #2: C library timing is repeatable but not accurate

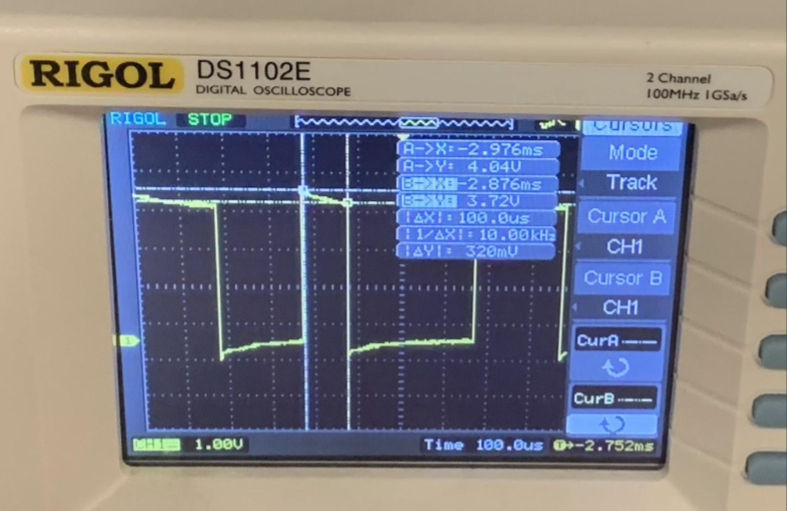

The exact pulse lengths of the signals sent to the laser are measured with an oscilloscope. When compared to the pulse lengths specified in the code, the measured lengths are longer, likely due to overheads in the code. When trying to achieve short/long pulse lengths of 100 us/200 us respectively, there was a 70us overhead in the observed pulse lengths. Thanks to the repeatability and precision of the C timing library, exact 100us/200us pulses can be achieved by simply subtracting this overhead.

Finding #3: C library timing cannot achieve delays below ~70us

The overhead of 70 us mentioned in the previous section did not change with the pulse length specified. Regardless of the pulse length specified, the actual observed pulse length was always roughly 70 us longer.

When the specified pulse length is near 0, the observed pulse length becomes roughly 70 us.

I hypothesized at one point that compiling with more performance-oriented optimization flags may decrease the overhead, but in practice compiling with the -O3 flag resulted in the same observed 70 us overhead.

The C library usleep (microsleep) and nanosleep functions are also functionally the same on the RPI. The nanosleep function nominally allows delays to be specified to the order of nanoseconds, but in practice the same 70 us overhead was observed. Nanosecond-level delays are simply not reliably achievable on the RPI + Linux combination.

Smaller delays could of course be done by, for example, writing an entirely useless for loop, but operations like this are entirely at the mercy of system scheduling, and the actual delay achieved is wildly unpredictable.

Still, reliably achieving 100us/200us pulses allows for a sizable speed increase from the previous configuration.

Finding #4: Interrupt handling on the RPI can be very limiting

In pushing the limits of transmission speed, interrupt-handling became the main limitation. According to oscilloscope measurements, if the voltage on the interrupt pin (connected to the diode) drops and then rises within several dozen microseconds, an interrupt is not triggered at all, and the listener thread does not get the information that the laser had stopped briefly.

This observation does somewhat line up with expectation, and the prediction in this post is not far off from my measurements.

In this regard, interrupt handling on the RPI is certainly greatly inferior to dedicated microcontrollers, and prevents the RPI from being useful for projects that require rapid event-triggering based on sensor data.

Take-away

The RPI + Linux combination is, as expected, not ideal for timing-critical projects, especially when interrupt triggering is an important feature. However, experiments show that its timing accuracy is still at a usable state, being below 100 microseconds. In this setup, the RPI + Linux combination achieves a transmission rate of 4 Kb/s on a simple laser + diode setup, which is a respectable standard.