Wasserstein Vs Dynamic Time Warping

Wasserstein distance vs Dynamic Time Warping

In my internship with UCSF Neuroscape lab, I was faced with an important question: is there any difference between Dynamic Time Warping and the Wasserstein metric applied on one-dimensional (time series) data? The end-goal here is to find an algorithm that could reliably determine how similar the body motion of an older adult is to young adults, but this question of DTW vs. Wasserstein applies to all time series comparison problems.

Background

Time series data is everywhere: stock information, temperature graphed over hours, and video are all time series, as they all are a series of data points linked in time order. For stocks, the price points of each day are linked; the temperature of each hour is stringed together; individual frames are linked together chronologically to form videos.

Dynamic Time Warping, an algorithm that uses dynamic programming, had been a leading time-series analysis algorithm for several decades, being used in a wide array of applications. As the name suggests, DTW “warps” the time coordinates of the time series in order to see similarities, even if the two series are not entirely aligned – a very useful trait.

However, another family of algorithms have just popped up – Optimal Transport. In the recent years, OT, and especially its Wasserstein distance, have become incredibly hot in Machine Learning, finding itself employed in roles from image searching to the discriminator of Generative Adversarial Networks.

Although Wasserstein distance (also called EMD) is nearly exclusively mentioned in the context of ML topics, when applied on time series data, it has an effect incredibly similar to that of DTW, also diligently warping coordinates to find similarities between series.

All of this begs a question – exactly how similar are Dynamic Time Warping and ML’s Wasserstein metric? Through looking into the two algorithms and performing real life testing, we find that DTW is nearly a 1-dimensional special case of Wasserstein metric, but is different in two ways.

Dynamic Time Warping

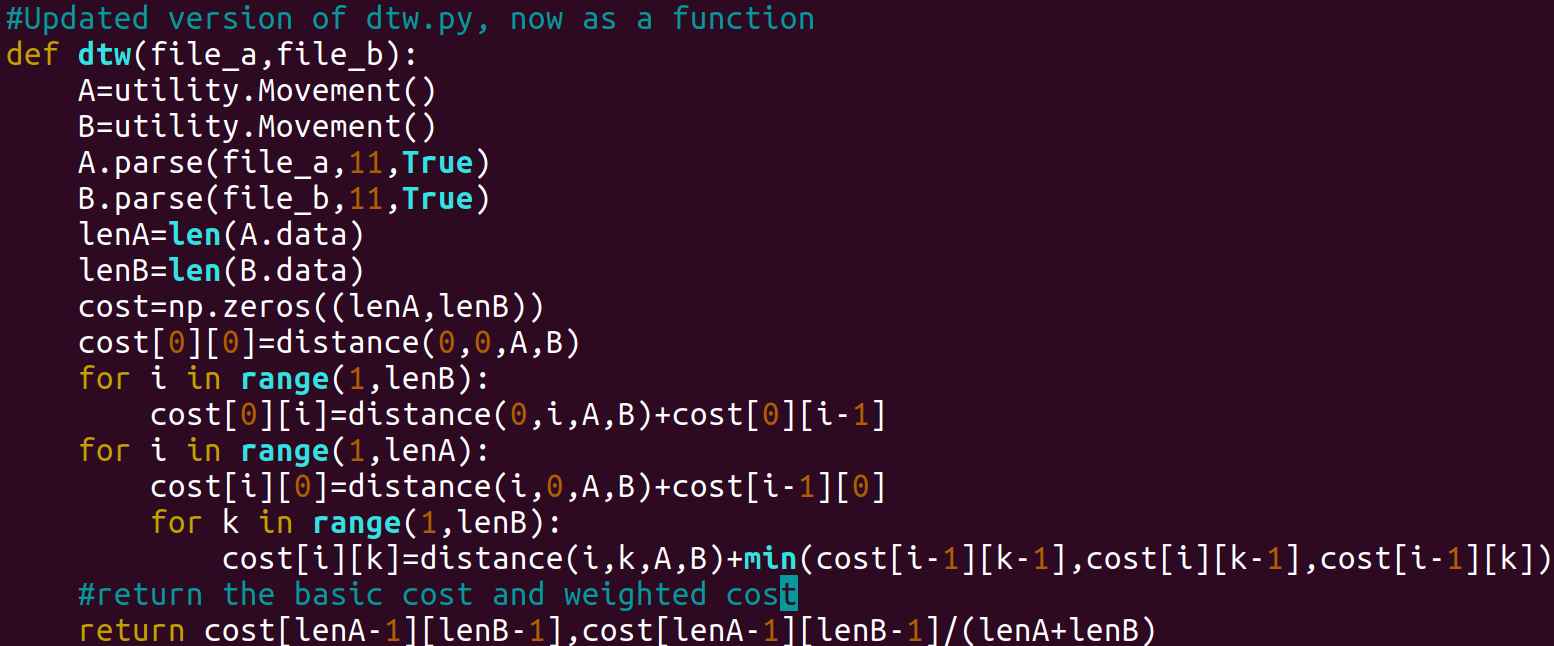

Dynamic Time Warping is a wonderfully simple algorithm, utilizing a two-dimensional array for the entire computation. Each state is the minimum of three possible cases: advance, insertion, or deletion, and the final cell of the array is the answer. Python code for DTW is incredibly simple, as seen below:

The line containing the “min” operation is the crucial status update

The line containing the “min” operation is the crucial status update

Wasserstein Metric

The Wasserstein metric is a much more general method, being able to compare the similarity of two arbitrary probability distributions, not just time series (data organized on one dimension).

The core concept here is transportation: how costly is it to change one probability distribution, so it becomes the other distribution? The more costly this transformation is, the less similar the two distributions are.

Being a far more general algorithm, solving for the Wasserstein metric is a much more complex process, a representative solution being the Sinkhorn algorithm.

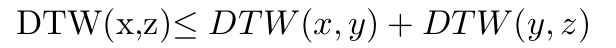

A key difference: metric

Crucially, DTW is not a metric, because it does not always satisfy the triangle inequality. In mathematical language, it means that the following isn’t always true:

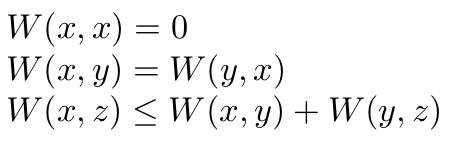

The Wasserstein metric, being a metric, satisfies all these conditions:

The Wasserstein metric, being a metric, satisfies all these conditions:

Wasserstein being a metric can be a major advantage in some scenarios. However, this isn’t the only difference between the two.

Wasserstein being a metric can be a major advantage in some scenarios. However, this isn’t the only difference between the two.

Chronological matching

Although DTW and Wasserstein metric have very similar effects on comparing time series, they come from different perspectives. DTW assumes that two time series being compared are of the same order, just with some segments compressed/expanded, and therefore employs dynamic programming to negate these compressions/expansions, while keeping the order of the series intact.

The Wasserstein meric, however, comes from a transportation perspective: the time series data is simply treated as a collection of each time-frame, and when transforming the time series, its frames do not have to be kept in order at all.

For example, if we take a video of 10 frames, A, and reverse the order of the frames to form video B, DTW and Wasserstein would produce very different results.

DTW would find series A and B to be not similar at all, as no amount of compressing/expanding parts of A will make it into B, since the frames are fundamentally out of order.

However, Wasserstein would find A and B to be identical, as each frame in A has a completely identical twin in B, so A can be turned into B without changing any of the frames at all.

(Note that here we are not specifying the ground metric, which is the measure used to determine how similar two individual frames are. No matter what the choice of ground metric is, the difference between DTW and Wasserstein remains.)

Of course, this is an extreme example, and in real world scenarios, the two methods often agree quite well, as the following experiment shows.

Applying on body motion data

Going back to the UCSF problem, we would like to compare two segments of body motion and output a similarity value.

Of course, would like to the comparison to detect similarities even if there are relative speed differences: if two motions are otherwise identical, but one is twice the speed of the other, we would still like the similarity to be high. Therefore, I turned to DTW and Wasserstein for help.

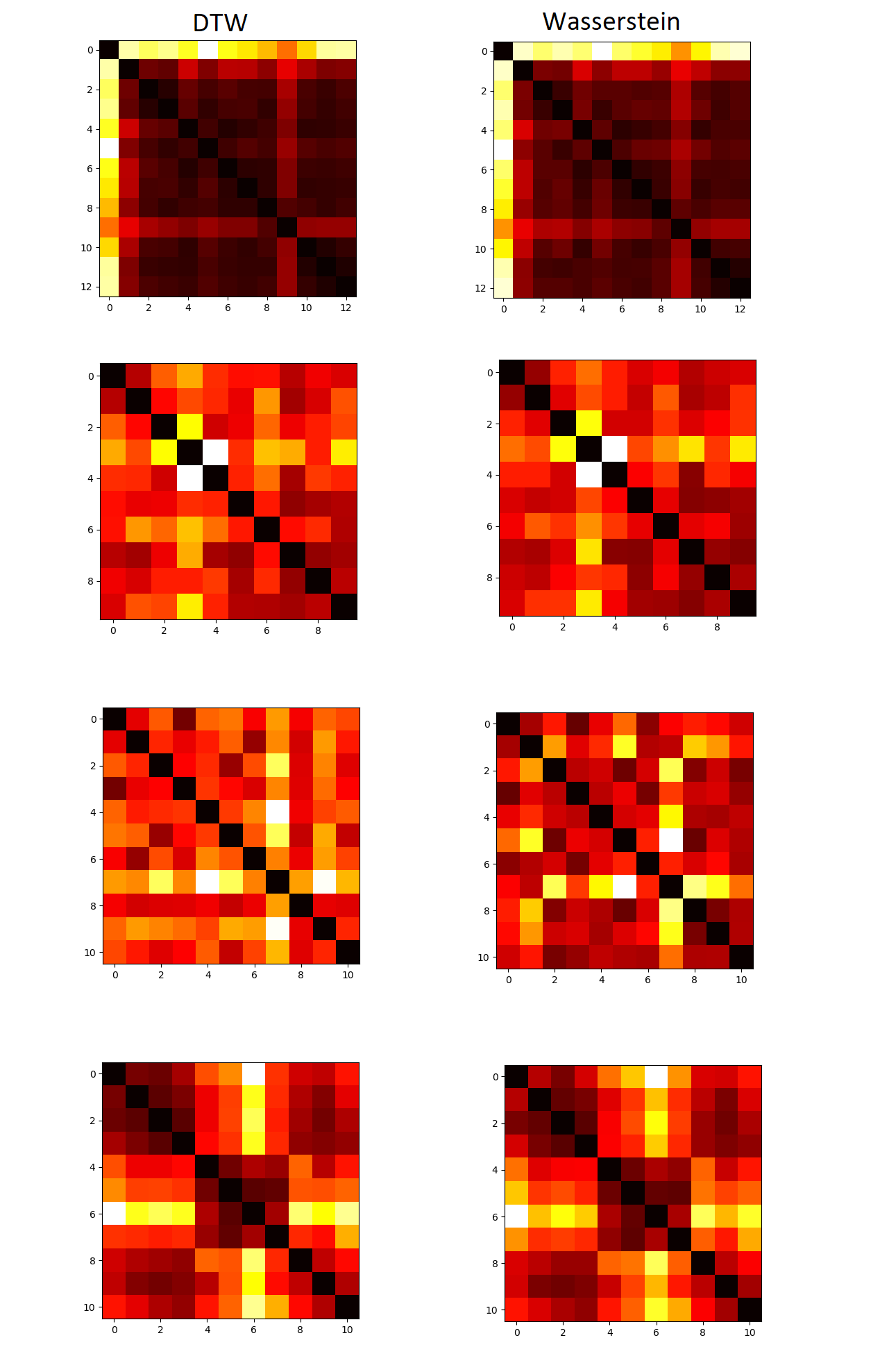

In a sample experiment, I used four “groups” of body motion segments, comparing segments in each group against one another using the two methods, and the results are visibly very similar. Here, (n,m) in a heatmap is the distance between segment n and segment m, as measured by DTW (left) and Wasserstein (right).

The r-value between the DTW distance and the Wasserstein distance is an incredible 0.98 out of 1, indicating a very strong correlation between these two distances.

There are indeed very minute differences between the distances calculated by the two, which could be attributed to the chronological matching difference as described before.

There are indeed very minute differences between the distances calculated by the two, which could be attributed to the chronological matching difference as described before.

Conclusion

Through testing on body-motion data, we confirm that DTW is very nearly a time-series (one-dimensional) special case of the Wasserstein metric, but there are two key differences separating the two:

- Metric: DTW does not always satisfy the triangle inequality, but Wasserstein maintains this inequality faithfully

- Chronological matching: DTW maintains the order of time series when conducting comparisons, while Wasserstein freely changes the order in search of a more efficient transformation.